INTERVIEW WITH BELINDA SALLIN,

DIRECTOR

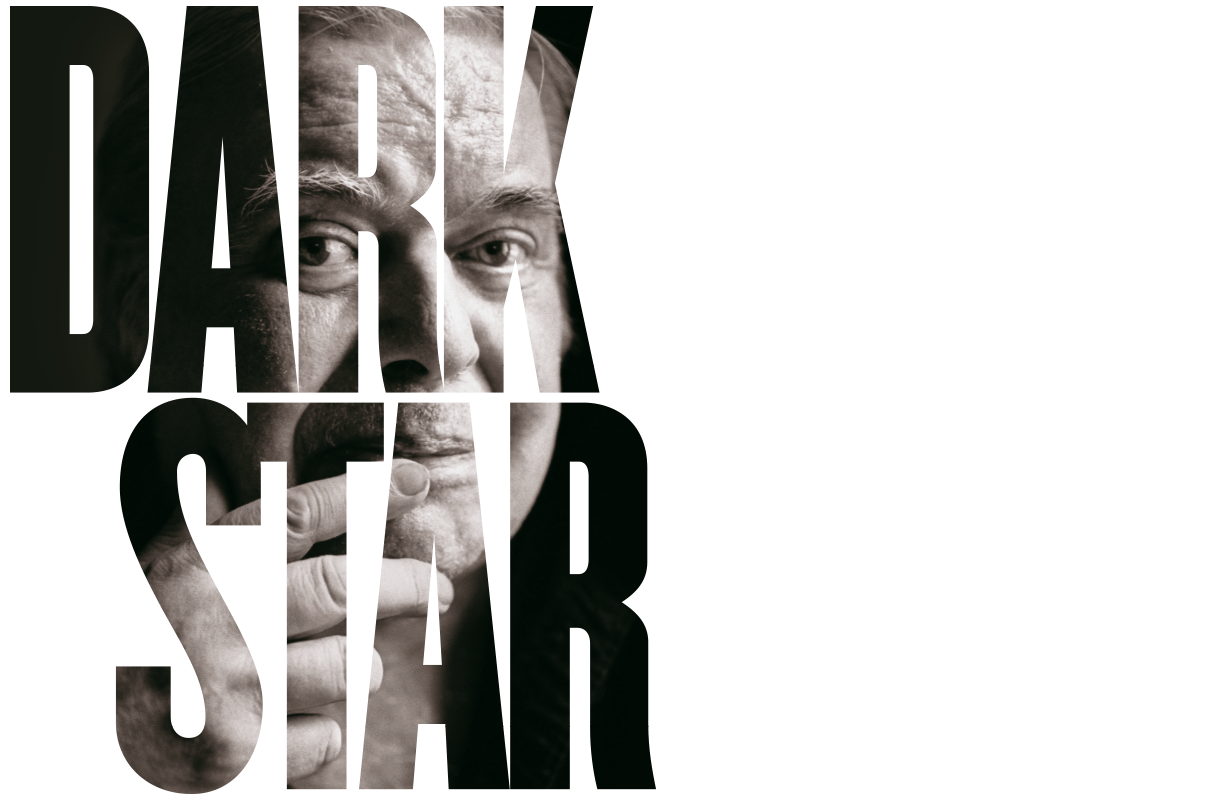

How did you come up with the title?

After the first few times I visited him in Oerlikon, Hansruedi seemed increasingly like a fixed star to me. He stayed in his house, hardly ever leaving. He could only be lured out of his house for a meal at a nice restaurant, or for one of his responsibilities of course, like a book signing or an exhibition opening. Otherwise Hansruedi stayed in his house, that very unusual home of his.

Anybody who wanted to visit Hansruedi or plan an exhibition with him, publish a book or make a film with him, as I did, had to go to Oerlikon. There Hansruedi would sit at the kitchen table, master of his own world. His friends, assistants or business partners all orbited around him like satellites. That’s how the title came to me: Hansruedi, the Fixed Star of his World, a Dark Star. DARK STAR – HR Giger’s World.

There was also a film in the '70s entitled Dark Star, directed by Dan O’Bannon. O’Bannon became a good friend of Hansruedi in the late '70s. He wrote the script for Alien. When Ridley Scott set out to find an artist to draw and design his monster and the alien planet, O’Bannon showed him Giger’s book “Necronomicon”. All Ridley Scott said was, “That’s it!”. Shortly afterwards, Scott, O’Bannon and Giger wrote film history together. I really like the fact that our film title includes a reference to that time.

Did you have to convince HR to do the film project?

I didn’t have to convince HR. It was high time for a project like this. I got the idea from Sandra Beretta, a former life partner of HR’s. She introduced me to him. I think that’s why I was able to gain HR’s trust rather quickly.

At first HR thought I wanted to do a TV documentary about him. When I told him I wanted to make a 90-minute feature documentary, he was amazed. In his own brand of humility, he asked me if perhaps other Swiss artists might be more “deserving” of a feature film. I told him other people would make films about other Swiss artists. I was going to make a film about him. That was pretty much all the convincing HR needed. I think, despite his humility, he was pretty excited about the project.

I was very pleased in January 2012 when Marcel Hoehn agreed to produce the film. But financing the film proved to be a difficult task. We had a lot of frustrations and disappointments, and everything got quite drawn out as a result. Except for the shooting of the teaser in fall of 2012 – some of that footage went into the film because his health was better at that time – I couldn’t begin shooting until fall of 2013. Naturally I was worried because I could see that HR’s health was deteriorating.

How do you personally feel about HR Giger’s art?

Honestly, that was quite a concern of mine when we started the project: Did I want to focus so intensely on HR Giger’s work for such a long time? What kind of feelings would that trigger in me?

Today I can say that taking that time to focus on HR’s art was definitely worth it. It certainly worked to my advantage – especially during filming – that I had no choice but to intensely study certain images. That way I was able to engage with the images, to overcome my own boundaries and leave my prejudices behind. It was interesting that many of the HR’s more figurative images tended to inspire abstract, philosophical thoughts in me, or very personal ones: What are my fears? What is evil and how does it manifest itself? How can I overcome it, etc.?

As a journalist, when I deal with the darkest sides of humanity -- with war, torture, abuse and things like that -- I have this great need to collect as many facts and understand as many connections as possible. Sometimes the horror is so great that I cannot or do not want to deal with it in another way. Hansruedi’s work could serve as a bridge to those questions. I think the aesthetics of his work may help. HR visualizes fears in such a way that after a while, if we engage them, we no longer have to fear them, but we can accept them.

I also found it interesting that some of Hansruedi’s work would change after I looked at them for a while. Suddenly, the creatures that seemed evil at first glance didn’t seem quite so evil anymore. They looked more helpless, lonely, pitiful, or even beautiful and elegant. I think it’s extraordinary how Hansruedi could depict the duality of existence: death and birth, Eros and Thanatos, everything being one and mutually dependent.

What do you think about the accusation that HR Giger’s work is sexist?

Some of the images are explicitly sexual, but they’re not at all sexist in my eyes. If I saw the images as sexist then I wouldn’t have been able to make the film. For me, sexism means the devaluation and discrimination of a person based on their gender. I don’t see that in Giger’s work.

I can understand that some men might feel threatened by the numerous phallic symbols. Or that some women might be annoyed that many of his female figures are exaggerated, beautiful, mystical or erotic looking, and that they make use of stereotypes to a certain extent. But you can’t go around blaming Giger, or any other male artist for that matter, for being a child of their time and for portraying women as beautiful. If that were a criterion of art history, we’d have to clear out more than half the museums.

In my opinion, the female figures and phallus symbols transcend the figurative and portray the primal instincts and forces of humanity. I can’t find any disparity in favour of one gender or the other. In fact, I think self-determination and emancipation take a back seat in all the figures in Giger’s work. For instance, they’ve been thrown into this inhospitable environment, completely dependent on machines or exoskeletons to survive. Or the figures are fully embedded in a huge circuit comprised of sexuality, death and birth. Of course Giger’s depictions are meant to be provocative. Hardly any other artist in history has ever grappled so intensively with these taboos and their interrelationships as he has.

So I think that as far as Giger’s work is concerned, any accusation of male chauvinism or sexism is completely inappropriate. Both viewpoints are equally superficial and completely miss the point.

What was it like shooting with HR Giger?

I found shooting with him to be very special. HR Giger’s health was weak. That meant that he was only available for very short periods of time. I really had to carefully consider what I wanted from him, and decide which scenes I definitely wanted to shoot with him. Then we discussed each scene in great detail with the crew beforehand, sometimes even acting them out on camera. Interestingly enough, the scenes took on – despite these preliminary talks - a very documentary, very authentic feeling with HR, in my opinion. We all knew there was only this one take, no retakes, no discussion or direction. I give HR a lot of credit for almost always conforming to my wishes. He often dutifully did his part in order to make this film a reality. But it was a new experience for him to have a crew work on a film about him for such a long time. HR had seen dozens of TV crews come and go. A few quotes, a few shots, and that was it. He repeatedly asked if we need to shoot that much. But in the end, he always seemed to be understanding when it came to my requests.

I often felt a kind of finality sneaking up on me while we were shooting. For instance, when we were up on the Alp Foppa, somehow I just knew it would be the last time HR would return to that place of his childhood.

In Linz, at the exhibition opening, I also asked myself if he’d be making many more trips like that. I still remember saying to my producer that if we wanted to make a film about HR, we’d have to film that exhibition because he might not be able to handle such strain for much longer. I’m very grateful that, despite our precarious financial situation, Marcel Hoehn took a chance and agreed to start filming at that time. It’s very important to the film that we were able to document that last journey and that exhibition with HR.

But I never dreamed HR would visit his museum for the last time with us. Actually, he didn’t really feel like going to Gruyères. After all, it was pretty taxing on him. It took a great deal of persuasion on my part. In the end, he only spent a short time in the museum. He didn’t want to stage anything at all, but we managed to film him in his beloved Spell Room for a few minutes.

I asked myself many times during the shooting if it was a good idea to make a film with a protagonist who hardly likes to speak anymore and who is withdrawing from the world more and more. In hindsight, I think maybe it was an asset to the film. Filming with HR was very condensed. There was never too much, never any rambling, never an unnecessary word. I think you see it when you watch the film.

What kind of relationship did you have with HR?

Our relationship was characterized by mutual respect. Because HR was often tired and didn’t want to speak very much, we didn’t talk for hours or have deep discussions. But I paid him many short visits in Oerlikon and we always got along quite well. We were on the same wavelength somehow, so we didn’t need to speak much.

In addition, he had never liked speaking about his art. Once he told me, self-ironically, that he never would’ve gotten very far on talking alone. I immediately accepted the fact that it wasn’t his medium and that I’d have to use other ways and means to realize the film. I think HR was relieved when he realized that.

I experienced HR as a very polite, charming and considerate person, right till the end. You could tell from his manners that he came from a good, middle-class home. He was the complete opposite of a lout. I liked that.

Of course I never experienced his other side, the side of the artist who selfishly pursues his goals. But I did see how indignant he could be if something didn’t meet his expectations -- for example, if a painting wasn’t hung just right or when a lamp in the museum was broken. The perfectionist in him didn’t like that one bit. He could turn right around and abandon an entire film crew. That was one of the reasons why our shoot in the Museum in Gruyères was so short. It was pretty nerve-wracking.

But all in all, we had a good time. HR was an extremely witty person who took his work more seriously than he took himself. I don’t know if his wit, his humility and his modesty had increased with age or if he’d always been that way. Interestingly enough, I recognized those same character traits in the early films, for example in one by Fredi M. Murer that was shot in the early '70s -- a timid artist who shied away from the limelight. After the huge publicity that came with winning the Oscar, HR apparently had to push that character trait into the background for a while. There were times when he didn’t seem truly authentic to me back then. I really appreciated meeting an older HR Giger who so closely resembled the way I had perceived the young Giger in the early films from the '70s: authentic, down to earth, very honest. It’s quite possible that he’d been that way all his life, but that the media had made him out differently. I can’t gauge that, having met him only two and a half years before his death.

What impressed you the most about HR?

That he had realized his dreams, regardless of what people thought or said. I can only imagine what kind of an affect his images had on people in the late '60s and early '70s. Whatever. He stuck to his own path.

Artists have no place in Hollywood? Whatever. He jumped at the opportunity to be able to portray his world three dimensionally.

The well-established galleries don’t want to show his work? Whatever. He built his own museum and become the lord of a castle in the process, thus fulfilling another childhood dream.

I think that someone who stuck to his own path without becoming hardened (he had to handle a lot of prejudice) and bitter (he never received the acknowledgement he desired) deserves a lot of respect.

What was it like for you when HR died during the postproduction of the film?

It was sad and, despite the fact that we were aware of Hansruedi’s health issues, it was shocking as well.

I know he was excited to see the film. He asked me more than once when it would be finished. I’m very sorry that he’ll never get to see it. Of course I would have loved to know what he thought of it. He would’ve been our first viewer.

It wasn’t easy emotionally to get back into our work rhythm. We were practically paralyzed in the beginning. It was also very strange that Hansruedi lived on in our editing suite, as if nothing had happened. Sometimes I would completely forget that he was gone.

It didn’t have much influence on the production side of things. We’d finished filming after all. We even managed to do the photo-shoot for the film poster, just five days before his death.

What do you hope to achieve with the film?

I want the film to be an honest portrayal of the man Hansruedi Giger and of his work. A portrayal as free as possible from prejudices and moral conceptions. A portrayal that takes the multitudes of different clichés that were piled on to Hansruedi all his life, and obliterates them.

No matter what you think of his art, it’s undeniable that HR Giger was an exceptional artist. He was unique, unmistakable and he had gigantic international charisma. He touched countless people all over the world with his art. There aren’t too many Swiss artists you can say that about. That’s why I hope the film sparks a new, unencumbered dialogue about HG Giger and his work.